Dr. Peter Safar (a Retrospective): The Forgotten Heroes of Freedom House

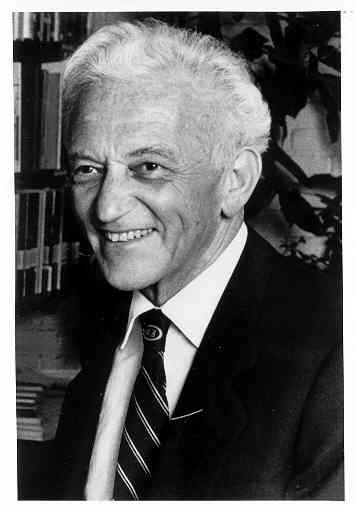

Our founding chair Dr. Peter Safar documented the first 15 years of the department (known in the beginning as the Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine (CCM), before CCM broke off into its own department in 2002) in a 1976 book currently housed in the University of Pittsburgh’s Health Sciences Library. The book reveals historical struggles and fights to establish order, policies and needed changes within the University, UPMC, the local community, and even the nation. Many of Dr. Safar’s tremendous accomplishments are well known – he is considered the “Father of CPR”, was a three-time nominee for the Nobel Prize in medicine, and established the first ICU in the US. One of Dr. Safar’s lesser-known accomplishments is his role in establishing Pittsburgh’s Freedom House Enterprise Ambulance Service.

Our founding chair Dr. Peter Safar documented the first 15 years of the department (known in the beginning as the Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine (CCM), before CCM broke off into its own department in 2002) in a 1976 book currently housed in the University of Pittsburgh’s Health Sciences Library. The book reveals historical struggles and fights to establish order, policies and needed changes within the University, UPMC, the local community, and even the nation. Many of Dr. Safar’s tremendous accomplishments are well known – he is considered the “Father of CPR”, was a three-time nominee for the Nobel Prize in medicine, and established the first ICU in the US. One of Dr. Safar’s lesser-known accomplishments is his role in establishing Pittsburgh’s Freedom House Enterprise Ambulance Service.

In 1967, nationwide emergency medical service standards were in dire need of reform, especially in Pittsburgh. The police officially ran the city’s ambulance service, and routine transfers were handled by mortuary rigs. The situation in Allegheny County and the rest of the nation was similar; ambulance services were run independently by volunteer firefighters, funeral directors, and private companies. These police and fireman were not medically trained, and their ambulances had little, no, or outdated equipment. Many patients died en route to the hospital. Former Pennsylvania governor and Pittsburgh mayor David L. Lawrence was no exception; in 1966 he suffered a heart attack while giving a speech and was taken to the hospital in a police emergency wagon. A nurse who just happened to be in the crowd performed CPR and accompanied Lawrence during the transport, only to find a broken inhalator/resuscitator in the ambulance; the vehicle also swayed and rocked so much during the ride that she kept losing her balance and was unable to continue CPR. While doctors were able to resuscitate Lawrence when he finally arrived at the hospital, his brain had gone too long without oxygen, and he suffered permanent brain damage. He never regained consciousness and died two weeks later.

Racism also plagued Pittsburgh, and many ambulance drivers simply refused to go to economically disadvantaged and predominantly African American neighborhoods, such as the Hill District.

Phil Hallen, president of the Maurice Falk Medical Fund, had a unique idea to start a private ambulance service in Pittsburgh’s Hill District. He presented his idea to Presbyterian University Hospital (now part of UPMC), who introduced Hallen to Dr. Safar. Safar had already been fervently campaigning for national and local ambulance design standards and medical training for ambulance workers for several years. But he was constantly halted by roadblocks when negotiating with local organizations for a grant to standardize emergency services in Allegheny County. Physicians felt only they were qualified to provide medical care. Allegheny county volunteer firemen resented having to take training and feared they would be put out of business. The mayor passed the buck, claiming emergency services were a county responsibility.

Phil Hallen, president of the Maurice Falk Medical Fund, had a unique idea to start a private ambulance service in Pittsburgh’s Hill District. He presented his idea to Presbyterian University Hospital (now part of UPMC), who introduced Hallen to Dr. Safar. Safar had already been fervently campaigning for national and local ambulance design standards and medical training for ambulance workers for several years. But he was constantly halted by roadblocks when negotiating with local organizations for a grant to standardize emergency services in Allegheny County. Physicians felt only they were qualified to provide medical care. Allegheny county volunteer firemen resented having to take training and feared they would be put out of business. The mayor passed the buck, claiming emergency services were a county responsibility.

Hallen and Safar recruited James McCoy Jr., founder of the Hill District’s Freedom House Enterprise Corporation, and Morton Coleman, an aide to the Pittsburgh mayor and part-time social work professor at the University of Pittsburgh. Their plan was to recruit uneducated, unemployed African American men for medical training to run an ambulance service in the Hill District. The project gave them the chance to try out Dr. Safar’s ideas for pre-hospital emergency care, combat racism, provide better job opportunities to unemployed African Americans, and improve services in a minority neighborhood.

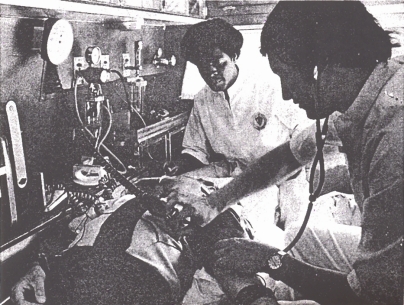

The group brought Hallen’s idea to fruition and in April 1967, the Freedom House Ambulance Service Committee held its inaugural meeting. Dr. Safar’s first class of 20 African American men graduated the first round of medical studies and began nine months of on-the-job training, running two second-hand police ambulances donated by the city. In their first year, Freedom House Ambulance Service made 5,868 runs and transported 4,627 patients, responding to an average of 15 calls a day, with a DOA record of only 1.9 percent. Pretty soon Freedom House was serving not only the Hill District, but the entire city of Pittsburgh. The Freedom House crew were the nation’s first paramedics, literally setting the standard for emergency care for the entire nation. Hallen, Safar, McCoy, and Coleman’s experiment pioneered a whole new profession – the EMT. More than 50 Freedom House paramedics and dispatchers handled more than 45,000 emergency calls over their eight-year history. They were no longer running second hand donated police ambulances, but five mobile intensive care ambulances.

The revolutionary Freedom House experiment came to a screeching halt in 1975 when the City of Pittsburgh finally decided to launch its own ambulance service. They did not renew Freedom House’s contract and absorbed their assets. While a few exiting Freedom House staff paramedics joined the city’s ambulance service, none were given any special consideration for jobs. The ones who stayed on were forced to take new rounds of academic tests. The new ambulance service became mostly white.

Recognition of Freedom House as the first pioneers of emergency medical care is scarce. Try googling “Freedom House Ambulance Services” and you will see virtually no references outside the Pittsburgh media. One person who has made it his life’s mission to tell the Freedom House story is Pittsburgh native and Hollywood movie medic Gene Starzenski, who created a 2009 documentary, Freedom House: Street Saviors. Although Gene’s movie was an HBO Martha’s Vinyard African American Film Festival Award finalist, he’s been unable to find a distribution deal. The movie has only been shown at film festival screenings and isn’t available on DVD. Gene has invested his own money into completing and promoting the documentary. Gene interviewed Dr. Safar about Freedom House for the documentary before Safar’s death in 2003. The Freedom House story also came close to being made into a major studio motion picture, but the deal fell through. Since, Gene wrote his own screenplay and is still tirelessly campaigning to have the movie made.

The Freedom House story also lives on in Dr. Safar’s chronicles. The story is retold in his articles, books, and in a master’s degree thesis of a student who worked with him to revitalize Pittsburgh’s emergency services. Among his numerous groundbreaking medical accomplishments, Dr. Safar made sure that this story wasn’t forgotten.

References:

- Bell RC. The Next Page: Freedom House Ambulance -- 'We were the best'. Pittsburgh Post Gazette, October 25, 2009

- Blake SS, Ross, M. Freedom House: Documentary Tells the Story of the Nation’s First Paramedics—Trained by Pitt Physicians. Pitt Chronicle, January 29, 2007.

- Dyer E. Freedom House ambulance service saved the day for many. Pittsburgh Post Gazette, February 28, 2007.

- Freedom House "Feature Documentary Trailer". Accessed May 4, 2011.

- Freedom House: Street Saviors Documentary Website. Accessed May 4, 2011.

- Interview, Gene Starzenski, Thursday, May 4, 2011.

- Public health aspects of critical care medicine and anesthesiology. Peter Safar, editor. Publisher: Philadelphia: F. A. Davis Co., c1974.

- Safar P. The Critical Care Medicine Program: Meeting the Community’s Emergencies. Communique’ (University of Pittsburgh Health Center). P. 7, Vol. 1, No. 2, Summer 1972.

- Safar PM, Sands PA. University of Pittsburgh Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine: The First 15 Years 1961-1976. Publisher: Pittsburgh, Pa: Department of Anesthesiology, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, 1976.

- Sands, PA. Political roadblocks to implementation of emergency medical services in Allegheny County. 1973. Portion of master’s thesis for the University of Pittsburgh School of Public Health.